by Joan Hewatt Swaim, published in TCU Magazine, Summer 2002

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Willis Hewatt, hereinafter known as “Daddy,” loved poetry. Many an evening in our home on Rogers Rd., with homework done and without the option of television, my sister and I would snuggle up beside him on our living room couch and listen to him read from the several books of poetry we had on our shelves. His selections ranged from William Wordsworth and Rudyard Kipling to Robert W. Service, Edgar Allan Poe, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. His reading of Holmes‘ “The Chambered Nautilus” will be remembered by all who sat in his invertebrate zoology classes.

One of Daddy’s favorite poems was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Psalm of Life. I recall him reading it to me and my sister when we really weren’t old enough to understand its message, much less appreciate it. “…Bivouac of Life…,” “be a hero in the strife…,” “Life is real! Life is earnest!/ And the grave is not its goal;/ Dust thou art, to dust returneth,/ Was not spoken of the soul…” etc., etc., sort of wafted rhythmically into our ears and above our heads. But the stanza that reads “Lives of great men all remind us/ We can make our lives sublime,/ And, departing, leave behind us / Footprints on the sands of time/” always made me envision footprints on a wet sandy beach, and I could certainly relate to that.The sea and seashore with its myriad animal and plant secrets were revealed to me from very early childhood, and at every opportunity Daddy‘s first love of marine biology would find us seaside, searching among riprap, tide pools, and pilings for whatever moved or could be defined as living.

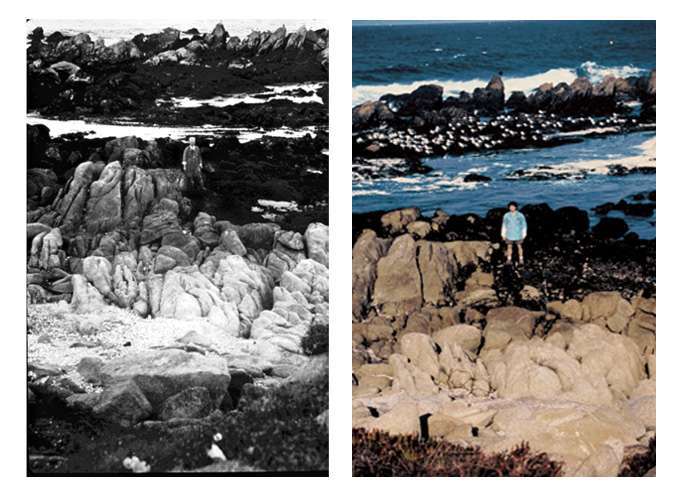

Daddy’s cadence intensified as he read those Longfellow lines, punctuating their importance. Those words and his voice still ring in my head. And, as it turns out, Daddy not only left his “footprints” on the “sands of time,” but someone searching for them sixty years later, actually found them, stepped into and followed them to a destination that may have far-reaching implications for how we manage our planet for sustainable life. The story of the discovery of the brass “footprints” and the intertidal “time” trail he left, and how that all came about is a fascinating one centering around three extraordinary scientists, each approaching the subject from slightly differing aspects.

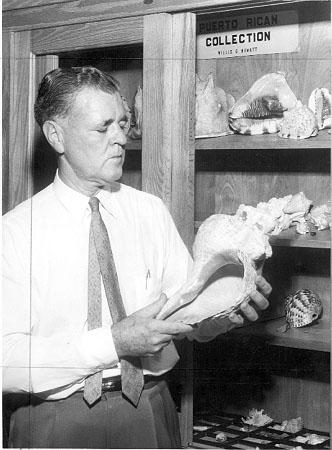

Although he ended up a land-locked scientist in Fort Worth, Texas, Daddy’s passion was the sea world of invertebrate life. How he discovered this passion is somewhat shrouded in the mist of Monterey, California. He was raised to manhood entirely in the Fort Worth area, the fourth of five children to his mother, widowed before the fifth was born. I am not sure that he ever was near the sea before he left TCU in 1931 to pursue his doctorate at Stanford University. I never questioned why he chose the marine scene. That was always who he was — a professor of biology at TCU during regular semesters and a specialist in marine biology on various coasts during the summers. No one I have queried from that period seems to have the answer, either. My guess is that he was “sent to” (read “placed at”) Stanford by Mr. Will Winton, his mentor at TCU, and once there, fell in love with the coast and opted for study at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station at Pacific Grove on the Monterey Peninsula, in turn falling in love with the various beauties of the salt-water “beasts,” as he called them.

That he did his study on the protected shoreline of Hopkins can simply be explained by the fact that he had no conveyance to, or equipment for, another location. I think he felt very fortunate to even be able to attend graduate school in the middle of a serious national depression. I have a poignant letter from him to his mother while at Pacific Grove, lamenting the fact that he could not help more with her finances and those of his own new family of wife and expected first child. He seemed to be barely able to subsist. Speculation could continue, but seems, in my view, unimportant here.

It was not until the spring of 2001, that I first heard of a young Stanford University doctoral candidate, Rafe Sagarin, who had replicated Daddy’s 1931-33 research at Cabrillo Point in Monterey Bay. It was as if Daddy was suddenly standing in the doorway. So unexpected — so strange to have him materialize in this way. I knew then that I would have to go meet these men who knew my father in an altogether different way than most who recall his memory to me. Rafe and his mentor, Charles Baxter, who had suggested repeating the earlier research, knew his intellect and work only. They had only a far-off snapshot of him in black and white. On my side, I had scanned his dissertation once and knew that it spoke to the adventures of the little homing limpet of the west coast, Acmaea scabra. I had no idea of the extent of the entire study. I wanted to “touch” this connection.

Ironically, they had tried to connect, also, at the time of the 1992 study, only to find to their great disappointment, that Daddy had died in 1980. Again, ironically, they found my website, but it had no addresses, and queries directed to TCU on my whereabouts went unanswered. Then, my cousin, Dale Gilliland, who lives in southern California, heard of Rafe’s study on the Jim Lehrer News Hour, contacted the TCU Magazine, who contacted me, and, as they say, thereby hangs the tale.

My daughter Susie, grandson Asher, and I made the trip to Pacific Grove/Monterey this past Easter to grasp yet another shoot of our roots. It was good to sit with all those connections on the promontory above the bay and talk the talk of the marine natural world with Chuck Baxter and Rafe Sagarin. Their words I had heard many, many times and many, many years ago in similar settings. I had danced happily to that rhythm before.

Daddy was good, but he wasn’t prescient. His work was about the ecological makeup of an intertidal transect off Cabrillo Point; global warming was a concern off in the future. Then, from the 1970s, Charles Baxter watched Cabrillo Point as its flora and fauna changed, and he grew suspicious of its cause. At Chuck’s suggestion and armed with the 1933 Hewatt guidelines, Rafe Sagarin took up the baton and waded, literally, into the issue of possible global warming and what it might mean for the natural world in which we live — three generations reaching across the years, helping, with their combined efforts, to find our way.

There is a kind of poesy there, methinks, that could fit right in with “heroes in the strife.” I know Willis Gilliland Hewatt would have thought so.

©2002 Joan Hewatt Swaim

Other related articles online:

- Conversations with a Tidepool, by Nancy Bartosek, TCU Magazine, Summer 2002

- Through a Fissure, TCU Magazine, Summer 2002

- Global Warming, Lessons Taught by Snails and Crabs, Science Daily, Nov 2000

- Tide Pools & Terrorists, Standford Magazine, Jan/Feb 2012

- Global Warming in Monterey Bay, PBS News Hour, March 2001

Be First to Comment